Contains Recursion

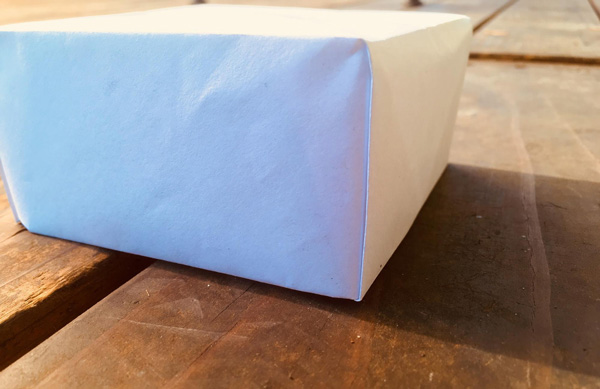

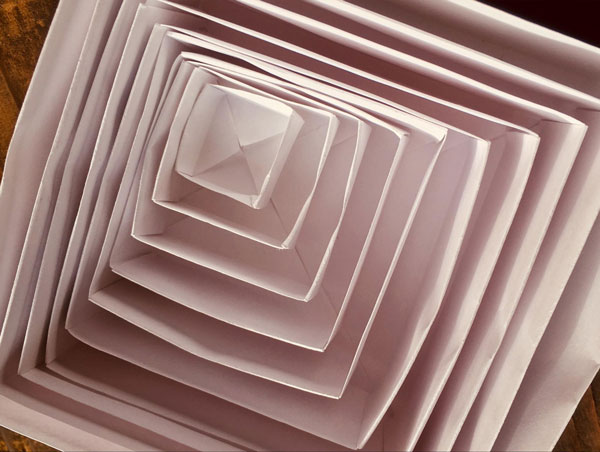

So there's this box.

And contained within it...

And within that box…

And on and on...

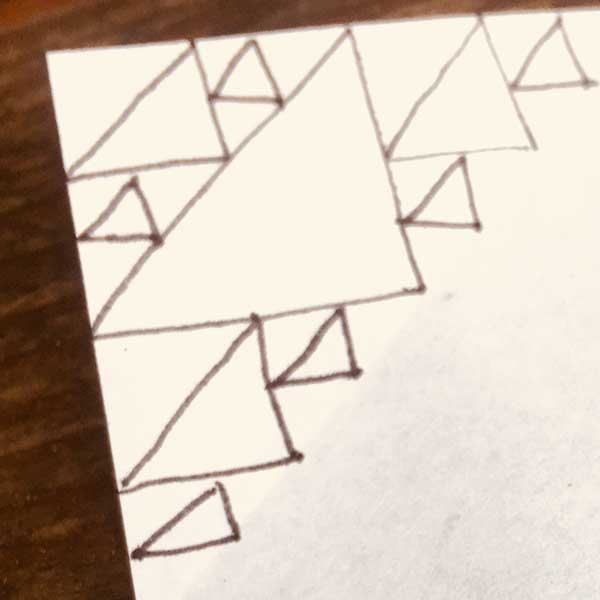

Like so:

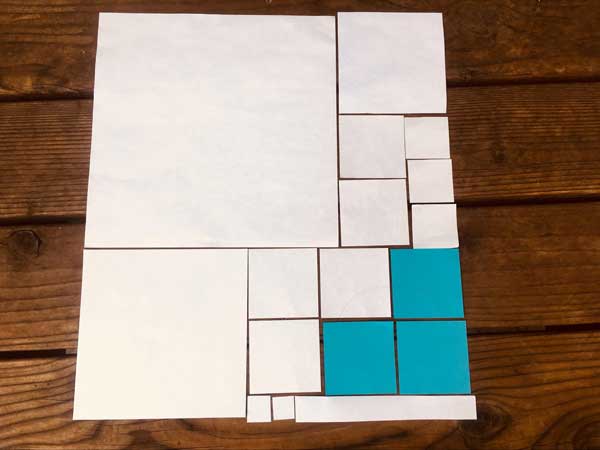

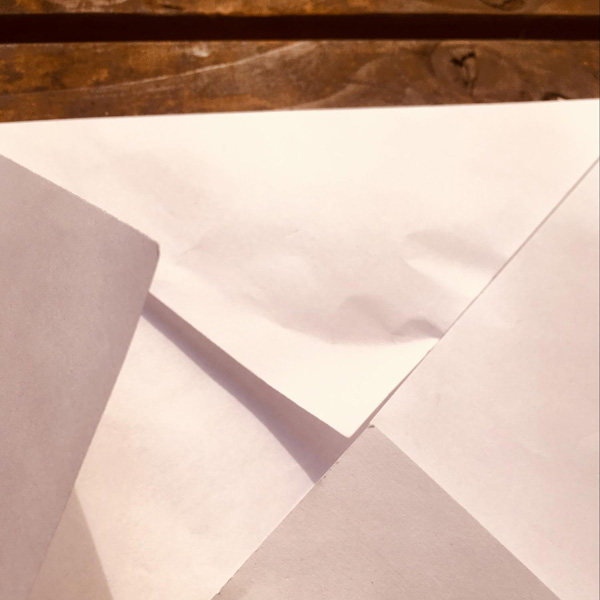

Before they were boxes, they were a giant rectangle.

This rectangle divided into ever-smaller squares.

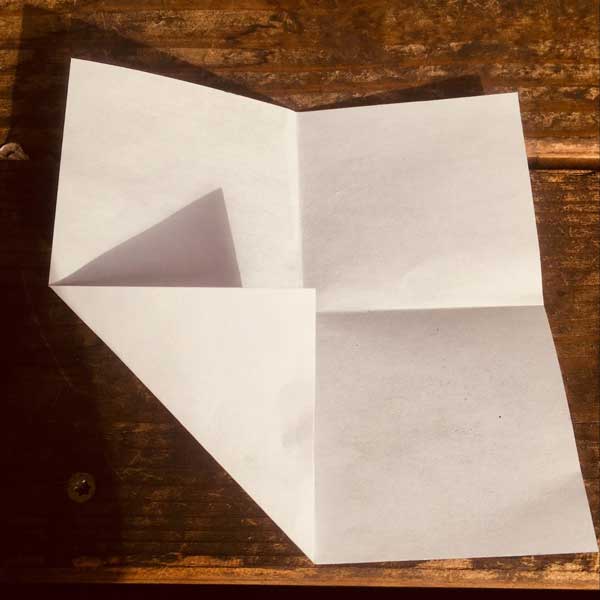

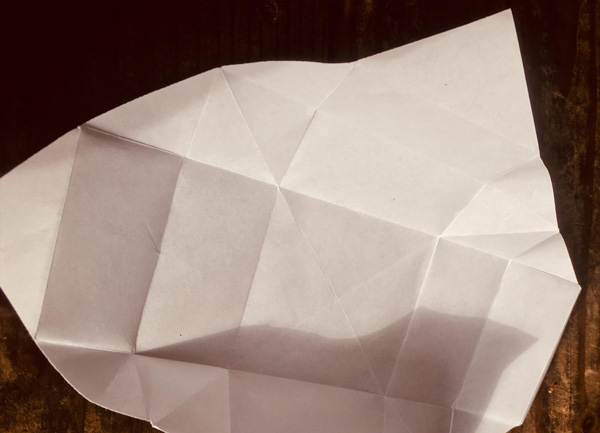

Creating the box from the square paper is a self-referential process: measurements for the folds are relative to the size of the paper. Each fold creates a new size of paper, which defines the scale of the next fold.

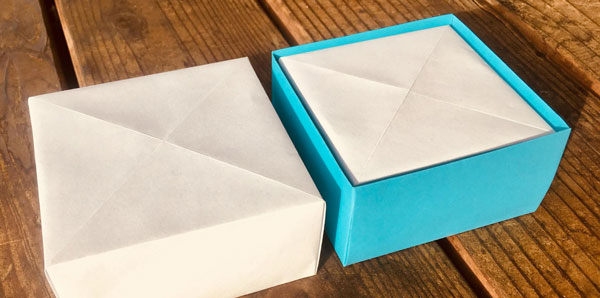

The boxes use their own form to hold their structure: a series of folding onto itself to create itself. No glue. No tape. No staples. It’s a self-reliant system: without one of the sides standing upright, all the other sides would swoop down. But if they all stand tall, then they all stand tall.

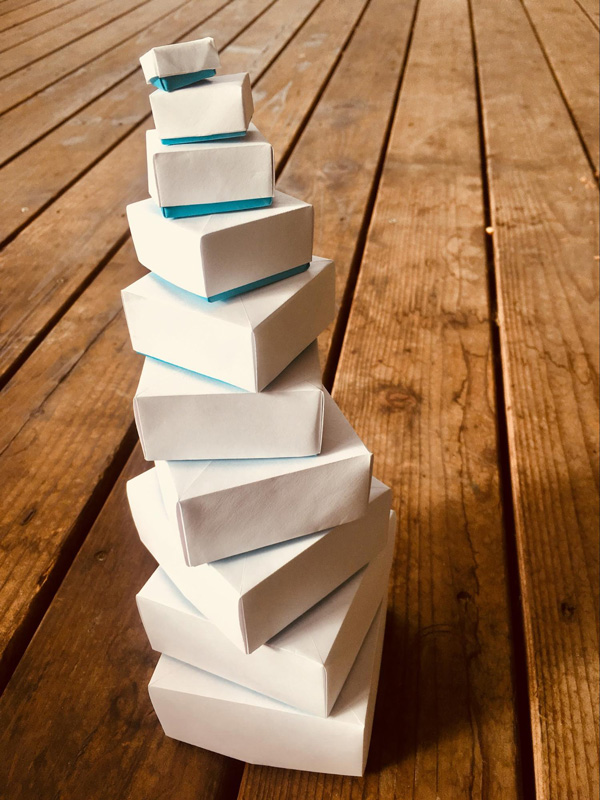

Sometimes the flaps flip up, threatening to unravel the whole contraption. What helps to secure that flap in place? Put another box in it!

The boxes within boxes diminish in size at an arithmetic rate, with some good old human-error variability.

Why spend twelve hours making hand-cut, handmade boxes instead of buying different sizes of perfectly pre-cut paper, or just posting an affiliate link to nesting boxes?

When we create objects by hand, we imprint a moment of our lives on them. The one with a messy spot records my time at a coffee shop, now forever a part of this piece of paper and no other piece of paper in the exact same way. The frazzled one is a timestamp of when I was tired and lost my concentration. The boxes store my thoughts, feelings and the schmutz on my hand of this particular moment. I make these containers. They contain components of me.

My fingers had forgotten how to make these. At first I fumble. A pile of wrinkled, confused papers grows.

Each time I repeat the process an additional tidbit embeds into my muscle memory: how to make a defined crease, or remembering to account for the lid being larger than the base. In this repeating process, box after box, they evolve from bumbling wrinkles to a recognizable set of shapes.

As I accumulate more box-shaping experiences to reflect on, the rhythm becomes intuitive, and I shape them almost on autopilot.

The momentum builds.

As my fingers repeat these motions, my whole body is on repeat. In this meditative activity, a new breath begins as each one concludes. And on it goes.

It’s not just the muscle memory that this folding marathon rekindles. A slew of box-folding memories that I’d forgotten I ever had pops into the forefront of my mind during the process. (Also this song. And an ensuing thought stream about city planning.)

The time when I learned to make these boxes emerges from a hazy memory into a clearer picture. I was in a particularly bizarre work environment. It was the era when I sang the Office Space soundtrack most mornings (this one in particular). I had a cactus on my desk in a can covered with purple glitter. I made paper cranes obsessively during meetings, mostly out of receipts from the cafe upstairs, each crane material evidence of my clinging to a bit humanity in an office that sucked souls dry. Beginning to fold again.

One day a coworker spotted the pile of cranes scattered across my desk. We had little in common, not even many words. He coached me silently through the box-making process so I could have a little nest for the growing herd of cranes. Now I remember. That was the first and last time I made these boxes. Until now.

That memory had faded over the years. Before I embarked on this box-making extravaganza I would not have been able to tell you where I first made a paper box (though maybe I would have confessed that this song came to mind). But as I repeated the motions, the memory folded into the present. As did more paper-folding memories than I knew I had: thousands of fundraising letters folded; the origami crane earrings I saw at a holiday sale after YMCA basketball practice in middle school - they enchanted me so much that I bought them a decade before I would get my ears pierced; the heart-shaped paper cutout that hung in my mother’s closet when I was a child, its origin a mystery to me to this day; the book my 4th grade teacher read out loud to us about a girl making a thousand paper cranes - the teacher cried and asked me to read the last chapter to the class. Now as I write this I remember I had planned to make a thousand paper cranes myself. I’d forgotten about that. Now I remember. A small basket near the kitchen table with fragments of Christmas paper converted into cranes so small I could barely hold them.

The folding continues. My present-day feelings about the past shift. Was that workplace more or less untenable than it seemed to me at the time? Would my experience in a similar situation differ now, having incorporated that and other experiences into myself in the meantime?

Beyond reframing memories and reshaping feelings, using my hands to create something ignites ideas about what I want to create next, sparking thoughts that I would not have had without going through this process.

With my box-making digits set to repeat, I now see that this project begs for additional layers. The colors of the boxes could alternate in a recursive pattern. We could tesselate a pattern onto the paper Sierpinski triangle seems a natural fit. When’s the last time I thought about tessellations - maybe decades ago in high school geometry?

But while the options of making things that fit into themselves are infinite, publishing deadlines are not.

And I don’t have a ruler.

So, onward! We’ll save some options for the next iteration.

I make these shapes, blemishes and all, that incorporate my own humanness at this moment. And they shape me, reprogramming my thoughts. We create each other. And now the song I loved in 11th grade comes to mind. (Wait, was that the year of high school geometry?)

The containers contained within themselves continue until we approach the the limits of my own dexterity and arrive at the final box.

It contains this.